Viva la Frida | The Life and Art of Frida Kahlo | A World Premiere Exhibition at Drents Museum in Assen, the Netherlands

Who is Frida Kahlo?

The Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), is without a doubt one of the most well-known and renowned artists in the world today. Her remarkable works of art, turbulent life, and unconventional lifestyle made her a global icon and cult figure. She suffered severe agony as a result of a tragic bus accident and had to endure multiple surgeries throughout her life. Her passion for art, her love for her husband, Diego Rivera, and Mexico's indigenous culture gave her the fortitude to persevere.

She made self-portraits with meaning that reflected her personal life. Her tumultuous relationship with Diego, as well as her broken body, inspired many of her works. She defied all social conventions and became a cult figure. Artists like Marina Abramovic, fashion designers like Dolce & Gabbana, Jean-Paul Gaultier, and Moschino, musicians like Madonna, and bands like Coldplay have all been influenced by her art and lifestyle.

‘Viva la Frida’ Exhibition in Drents Museum

Standing in a picturesque quiet corner of Assen, the capital city of the Dutch province of Drenthe since 1854, the Drents Museum is hosting a world’s first - a unique blend of Frida Kahlo's work and personal belongings from the world's two most prominent Frida Kahlo collections, Museo Dolores Olmedo and Museo Frida Kahlo (originally the Casa Azul or Blue House) in Mexico City.

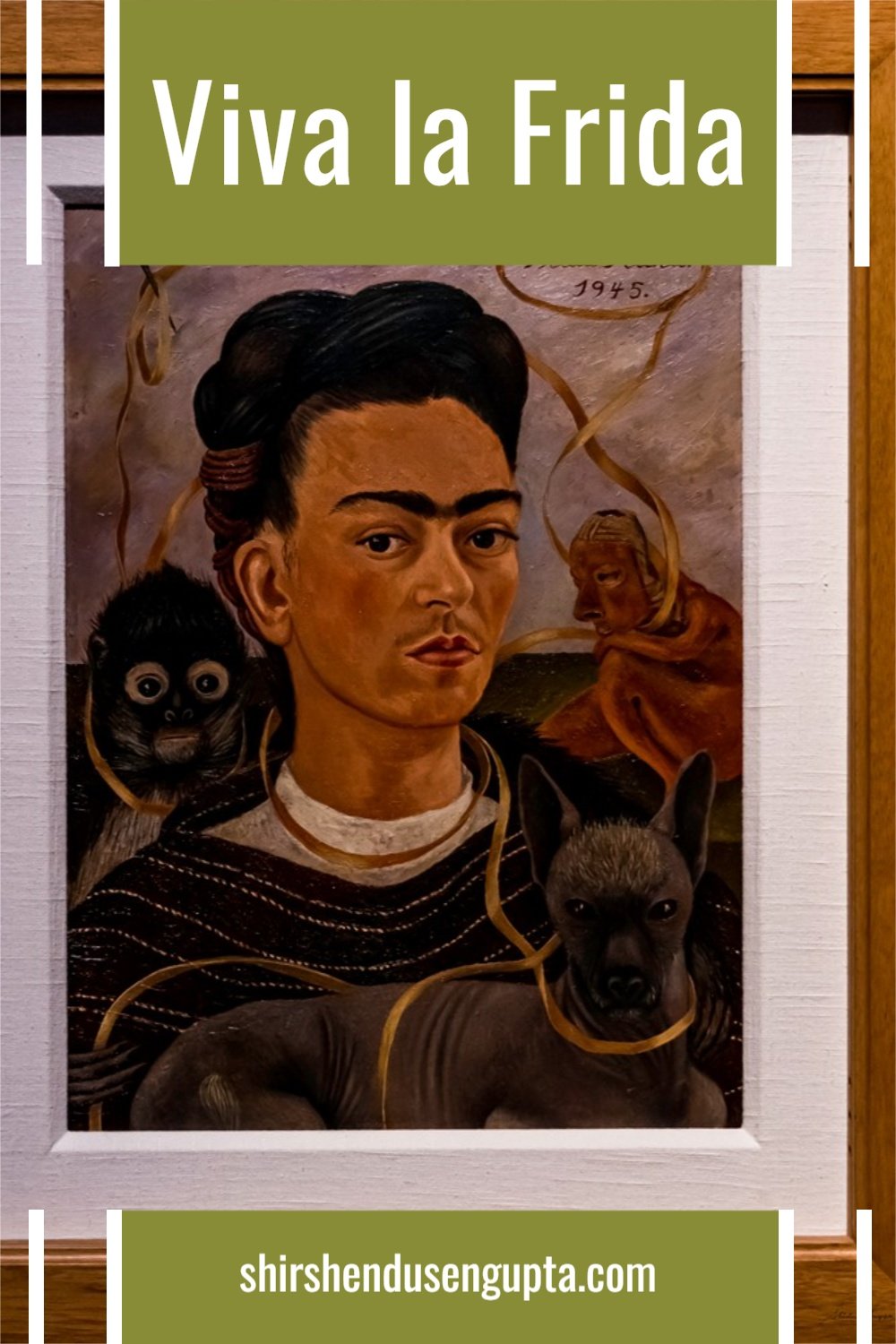

The Olmedo houses the world's largest collection of Frida Kahlo's work. Dolores Olmedo (1908-2002), was a Mexican woman who began collecting Frida's paintings in 1955 on the recommendation of her good friend and Frida’s husband Diego. In Assen, major works from the collection are on display, including Henry Ford Hospital (1932), The Broken Column (1944), and Self-Portrait with Small Monkey (1945).

Viva la Frida also exhibits the artist's costumes, painted corsets, and jewelry from the Blue House, where she was born, lied ill on the bed after the accident, created most of her art, and finally passed away. The house is known as the ‘Blue House’ since Frida and Diego painted the walls bright blue, decorated them with folk art, planted exotic plants, and kept parrots, monkeys, ducks, and a fawn, to emulate the Mexican paradise of their dreams. Following 50 years of captivity, many of Frida's and Diego's belongings were uncovered in late 2003 at the Blue House (now Museo Frida Kahlo). Following years of meticulous restoration, investigation, and curation, this extraordinary collection was made available to the public in 2007. Photographs, documents, and clothes, as well as several of Frida's personal belongings, sketches, and toys, are among the items on display.

The Life of Frida Kahlo through her Art

1. Early years (1907 - 1922)

Frida Kahlo was born in the Blue House on July 6, 1907, to a German father of Hungarian ancestry (Guillermo Kahlo) and a Mexican mother of Spanish and indigenous Mexican ancestry (Matilde Calderón y González). Frida was introduced to the traditional clothing style of women from the southeastern region of Tehuantepec by her mother. Later in her career as an artist, Frida explored her identity by portraying her ancestors as binary opposites: colonial Europeans and indigenous Mexicans.

During her childhood, Frida was particularly close to her father, a skilled photographer, and she often volunteered in his studio, where she developed a keen eye for detail. He took an innumerable number of her portraits as a child and taught her how to pose and smile, which’s known to have aroused her interest in self-portraits, an iconic style of art that the world would come to know her for later. He also inspired her to read great German authors like Goethe and Schiller. She once mentioned, “My childhood was marvelous because my father was a huge example to me of tenderness and work ethic, and above all in understanding all my problems.”

At the age of six, she contracted polio, which left her with a minor limp that she would have to live with for the rest of her life and wiped away the smile from her face in her portraits going forward. At the age of 15, Frida became one of the 35 female students accepted into Mexico City's prestigious National Preparatory School, a state-run post-secondary school with a student population of about 2,000. Despite taking some art classes, she was primarily interested in science and wanted to become a physician.

2. The Bus Accident (1925)

On September 17, 1925, at the age of 18, Frida met a horrendous bus accident. A tram struck the bus she was riding. As a result, a pole entered her from the stomach to the pelvis, causing catastrophic injuries to her body. Her body underwent severe torture, which included 32 surgical operations, various corsets, and mechanical "stretching" systems. Frida began painting during the period of her recovery while lying in bed.

Portrait of Alicia Galant (1927)

This is one of Frida's earliest portraits. It was her first actual painting, which she proudly labeled on the back: 'First painting by Frida Kahlo.' In this painting, Alicia Galant has regal charm with her gently shimmering velvet gowns and haughty demeanor. Despite this, she was just a regular student. Frida modeled her after the famous 16th-century European painters she had studied. Galant was a former student at the National Preparatory School, which she was no longer able to attend due to her accident. So she began portraying school friends shortly after her accident. They were closer in this sense, and Frida felt less lonely. She would sometimes give self-portraits to friends so that they would remember her.

3. Joining the Communist Revolution (1928)

Since 1910, the Mexicans stricken by poverty and oppression had waged a revolution against the elite. Frida, always felt to be a ‘Child of the revolution,’ so much so that she claimed 1910 as her birth year in solidarity with the revolution and often referred back to Mexican culture in her art. She joined the Mexican Communist Party in 1928 upon the insistence of the photographer and activist friend Tina Modotti. Modotti later introduced Frida to Diego Rivera, one of the most powerful painters of the 20th century. Diego depicted Frida as a revolutionary comrade dispensing guns in his mural ‘Ballad of the Revolution’ at the Ministry of Public Education.

Portrait of Tina Modotti, image source: theartstory.org/artist/modotti-tina

The Bus (1929)

Four years after the accident, Frida painted a bus scene. A middle-class lady resembling herself, a laborer in overalls, a barefoot mother with her infant, a white businessman, and a beautifully dressed young lady from the city are among the passengers on this bus: in a nutshell, Mexican civilization. The tiny child gazes out over a landscape where industry and nature collide. Frida appears to be advocating for the rights of Mexico's indigenous peoples. Their land had been taken away from them to make place for factories. It is unknown if Frida was referring to her tragic accident in 1925 when she made this. However, the inside resembles the wooden bus she was riding when it collided with a streetcar.

4. Marriage with Diego Rivera and resigning from the Communist Party (1929)

As a young artist, Frida approached Diego, and he recognized her brilliance and distinct expression as truly special and particularly Mexican. He aided her artistic development and developed an intimate relationship with Frida. Despite Frida's mother's objections, at the age of 22, she married Diego, who was 21 years senior to her, on 21st August 1929, to become his third wife. But her marriage with Diego did not turn out to be an easy one. Diego was charismatic and an incorrigible womanizer and Frida underwent terrible pain owing to Diego's multiple affairs, but her love for Diego remained steadfast. She later mentioned “I have suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. The other was Diego.”

Later that year, Diego got expelled from the Communist Party for accepting anti-communist commissions. In protest, Frida also resigned.

The Girl Virginia (1929)

With the lace sleeves, the connecting brows, and the safety pin that substitutes a missing button, Virginia was portrayed exactly as she was by Frida. She created a portrait of a genuine youngster, which was pretty unique. Children were depicted at the turn of the twentieth century, but not always with their own distinct traits. This is an early portrait in which Frida, among other things, experimented with her color palette. She drew a self-portrait on the back, which she later used as a model for a painting.

Nude study of my cousin Ady Weber (1930)

Ady Weber, Frida's young cousin, stands in this painting, her feet drawn separately from the rest of her body and floating next to her breast. It's unknown why this decision was made because Frida could have easily drawn the body in proportion to the size of the sheet of paper she was using without having any issues.

The Hand (1930)

Frida focuses on painting a realistic picture of her left hand in this drawing titled ‘ The Hand.’ Frida drew this sketch during a period of convalescence in which she engaged in a common and necessary habit of becoming her own model, depicted without the jewelry she loved to wear.

5. The First Miscarriage (1930)

Frida's pregnancy ends in failure due to a pelvic condition caused by the trauma of the accident.

6. First Trip to America - San Francisco (1930)

In the November of 1930, Diego was invited to make murals in San Fransisco. This was Frida’s first trip away from home. During this period, Frida kept herself occupied by drawing, painting, and going to museums, concerts, theaters, and films. She actively established her Mexican image with her clothing. She was once described as "Rivera's exotic wife who enthusiastically dabbles in art" by a newspaper, but in America, she blossomed into the artist we know today.

Portrait of Lady Hastings (1931)

Lord John Hastings' wife, Lady Cristina Hastings, assisted Diego on his murals in San Francisco. Frida and Cristina became friends and joined each other on outings. In the milieu of artists, photographers, and writers, Frida felt entirely at ease. She drew portraits of her new acquaintances.

Lady Cristina Hastings' aristocratic sophistication is captured in this lovely pencil sketch. She was born in Milan and educated at Oxford. Lady Cristina's demeanor interested Frida, who perceived her as someone who fluctuated between emotions of boredom, explosive fury, and laughter.

Nude of Eva Frederick (1931)

Frida made this drawing of Eva Frederick in San Francisco. On a classic Mexican chair, an African-American woman sits in a calm position. Imogen Cunningham, a photographer, introduced Frederick to Frida.

Portrait of Eva Frederick (1931)

The sitter's confident expression emanates from his or her outer look. “Portrait of Eva Frederick, born in New York, painted by Frida Kahlo,” reads the inscription on the banderole. Frida was fascinated by African-American culture and history throughout her life.

7. Hospitalization in San Francisco (1931)

In 1931, Frida developed acute tendinitis in her right leg and got hospitalized while still in San Francisco.

8. Return to Mexico and Affair with Nickolas Muray (1932)

Frida and Diego returned from San Francisco in 1932. Upon return, Diego employed Mexican architect Juan O'Gorman to create two linked houses and studios in Mexico City's San Angel area. It was during this period that Frida met Nickolas the first time who had traveled to Mexico on a vacation.

Nickolas, who was born in Hungary and pioneered color portrait photography, was a well-known artist in his own right. He photographed numerous notable figures from the political, artistic, and social realms throughout the course of his long career. Harper's Bazaar, Vanity Fair, McCall's, and the Ladies Home Journal all published his work on a regular basis. His body of work is huge, with over 10,000 photos in total. Nickolas photographed Frida more than any of his other subjects, and his pictures of her are among the artist's most iconic non-self-portrait photos. These images of Frida have appeared in a range of media and popular culture, and they are crucial to understanding who Frida Kahlo was as a person behind her art.

Frida and Nickolas went on to have an on-again, off-again relationship that ended in 1941 when Nickolas married. They were great friends for the rest of their lives. Frida once exclaimed to Nickolas “Nick, I adore you like an angel. You are a lily from the valleys of my love!”

Some of Frida’s Photographs taken by Nickolas

9. Second Trip to America and Affair with Georgia O’Keeffe - New York (1931)

Frida and Diego traveled to New York in November 1931 at the invitation of Frances Flynn Payne, the Rockefeller family's aesthetic consultant, for a solo exhibition by Diego at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which opened on December 22, 1931. It is there where Frida met the painter Georgia O’Keeffe. Both were bold, flamboyant, and very powerful personalities, and they were both female artists striving to make their mark while married to older, adulterous, powerful male artists (O'Keeffe's spouse was photographer Alfred Stieglitz) whose reputations at the time overshadowed theirs. It is rumored that they were involved in a romantic relationship for some time.

Portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe, image source: okeeffemuseum.org/about-georgia-okeeffe

Self-Portrait with Red Beret (1932)

Frida was a member of a group of students at the National Preparatory School known as "Los Cachuchas" because of the caps they wore. This unique club consisted of nine individuals who were exceptionally clever, involved in social and political concerns, and notorious for their naughty pranks. They gathered at various locations to swap books, especially those written in foreign languages like English and German, and to talk politics. Aside from their academic responsibilities, they also hosted intellectual competitions, recited poetry, and performed theatrical productions. Frida is portrayed in the artwork wearing the group's trademark hat.

Self-Portrait Dreaming (1932)

Frida is resting in her bed. Like ideas and sensations, lines snake out of her skull. Frida's symbolic self-portraits became more popular in America. They aided her in expressing her inner self.

Portrait of Luthor Burbank (1932)

Luther Burbank, an American botanist who dedicated his life to cross-breeding plants, was buried in his garden under a Lebanon tree. Frida was influenced by his beliefs. This painting is a homage to him. Burbank was depicted by Frida as a 'hybrid,' a mix of a man, a tree stump, a cadaver, and a live plant. "I would prefer the strength of my body to be absorbed into the strength of a tree," he had anticipated, and his own, now rotted body acts as fertilization here. New life has risen from the ashes of death. Burbank's scientific theories were often regarded as heretical, but they fascinated and liberated Frida. She could relate to his beliefs because she, too, felt that she was a "mixture."

View of New York (1932)

“New York is simply a marvel. It is hard to believe the city was built by humans, It appears like magic.” Frida adored New York, particularly the Metropolitan Museum and the Harlem district. However, she was struck by the huge inequity she witnessed there. "There is so much wealth and so much misery at the same time, that it seems incredible that people can endure such class difference, and accept such a form of life since thousands and thousands of people are starving of hunger while on the other hand, the millionaires throw away millions on stupidities.” Frida dedicated this sketch to Dolores del Rio who was known as one of Diego’s lovers but was also close to Frida who was known to befriend and charm her husband’s girlfriends.

Self-portrait on the Border of Mexico and the US (1932)

Frida stands in the center of the composition as Carmen Rivera. She separates it into two sections. She uses the Mexican flag to represent the country's crumbling archaeological past, tropical vegetation, and life and death motifs. Frida places the United States in opposition to Mexico. There are a lot of skyscrapers and factories. Because of the filthy air and numerous modern devices, nature appears to be far away. Both countries are compared and critiqued by Frida. Diego's exaltation of both the industrial north and the rural south is likewise undermined by her.

10. Moving from New York to Detroit and Second Miscarriage (1932)

Frida and Diego moved to Detroit in April 1932. The Ford Motor Company commissioned Diego to paint a mural for the Detroit Institute of Arts. When Frida arrived in Detroit from New York, she found out she was expecting a child. She admitted to trying to get an abortion in a letter to her doctor and friend Leo Eloesser. After that failed, she pondered having the baby nonetheless. However, Frida miscarried and nearly died as a result.

Henry Ford Hospital (1932)

In a startling self-portrait packed with symbolism, Frida conveyed the profound experience of her second miscarriage. It was forbidden to talk about your miscarriage, and it was much more so to paint it. Frida accomplished it, and she did it in a very personal and confrontational way.

On the sheets of a hospital bed, Frida is shown naked, sobbing, and hemorrhaging. Six objects float around her bed, connected to her by vein-like red ribbons, representing the feelings she felt during the miscarriage: a male fetus, an orchid that resembles a uterus, a snail meant to represent the miscarriage's slow pace, a medical model of a female torso used to illustrate anatomy, an autoclave (a machine used to sterilize medical instruments and that Frida invented the look of to explain the mechanical feeling of her treatment), and a pelvis bone. Her sense of loss and desolation is heightened by the harsh industrial landscape and the distant skyscrapers of Detroit.

Frida and the Miscarriage (1932)

Frida created her first and only lithograph five weeks after her miscarriage. Anatomical pictures, Aztec botanical designs, and cosmology are among her sources of inspiration. The lithograph depicts Frida naked with her unborn child evident in her stomach. The artist is holding a painting palette on the right side, which is darker and overseen by a crying moon. The ground underneath Frida is nourished by the blood that flows down from her. Splitting cells may be seen on the left, and a big fetus hovers in the bottom corner of the page, attached to Frida by an umbilical cord. The world of parenting appears to be separate from Frida's professional activity as an artist in this lithograph. The darker side of the painting emphasizes her child's death and the anguish it caused her.

Though Frida did not produce many prints throughout her lifetime, Diego pushed her to work on this lithograph in the aftermath of her miscarriage. She swiftly returned to the easel, despite the fact that the method had helped her deal with her despair at the time.

11. Moving back to New York from Detroit and failure at Rockefeller Project (1933)

In March 1933, Frida and Diego traveled back to New York upon getting commissioned by Nelson A. Rockefeller for painting a mural at the Rockefeller Center. But Diego's inclusion of the communist leader Vladimir Lenin in the painting got him fired.

12. Moving back to Mexico (1933)

In December 1933, Frida and Diego returned back to Mexico and settled in their home in San Angel.

13. The Third Miscarriage (1934)

Throughout her life, Frida yearned for a child and was heartbroken when she miscarried for the third time in 1934. Her health deteriorated as she also underwent an appendectomy and the amputation of gangrenous toes. Owing to her health problems, her marriage to Diego became strained.

Dr. Leo Eloesser’s letter to Frida (October 29, 1934)

In these difficult hours of her life, she received a letter from her San Francisco-based physician Dr. Eloesser. He wrote, "Your doctor embraces you, Friedita, with all his love.” Frida had a close relationship with Dr. Eloesser and they exchanged letters on a regular basis.

14. Diego’s Affair with Frida’s Sister Cristina and Frida’s Affair with Isamu Noguchi (1935)

Diego was unhappy to be back in Mexico, and he blamed Frida for it. Diego had previously been unfaithful to her, but now he was having an affair with her younger sister Cristina, which hurt Frida's heart greatly. She left Diego to live in a central Mexico City apartment after discovering the affair in early 1935 for several months and pondered divorcing him. During this time, she cut off the majority of her distinctive long dark hair. She also developed an affair with Isamu Noguchi, an American artist.

Portrait of Cristina Kahlo, image source: thearkofgrace.com/2017/07/27/cristina-kahlo

Portrait of Isamu Noguchi, image source: economist.com/books-and-arts/2021/07/31/isamu-noguchi-explored-what-it-means-to-be-a-global-citizen

A Few Small Nips (1935)

After learning that Diego was having an affair with her younger sister Cristina, Frida created this painting. Violence oozes through the painting, both literally and metaphorically. Frida pierced the frame with metal nails on purpose, leaving blooded paint smears and fingerprints all over it. This work is linked to Frida's feeling of being ‘murdered by life,’ according to art historian and biographer Hayden Herrera. Frida might have recognized herself in a newspaper tale about a man who stabbed his girlfriend. She captioned the image with the words used by the murderer to defend himself, that it was just ‘a few nips.’

15. Reunion with Diego and Cristina and end of Affair with Isamu Noguchi (1935)

Later in 1935, Frida reunited with Diego and Cristina and returned to her house. She grew close to Cristina's children, Isolda and Antonio, and became a loving aunt to them. Despite the reconciliation, Diego and Frida continued to be unfaithful to each other.

Diego kept taking new girlfriends and Frida’s sentiments towards Isamu grew strong: "You are to me every love thought," Isamu once wrote to her. Diego, on the other hand, remained envious of his wife's male associates. As a result, Frida and Isamu struggled to have a successful affair. According to one tale, Frida and Isamu attempted to share an apartment, but their intentions were thwarted when her husband received a bill for the furniture. On another account, Diego arrived home when Frida was in bed with Isamu. Isamu fled but left a sock behind, leading to Diego threatening him with his revolver. When Isamu went to see Frida in the hospital, Diego threatened him with a gun once more. In due course of time, the affair died down.

16. Back to Political Activism and Affair with Leon Trotsky (1936 - 1938)

In 1936, she returned to political activism and became a founding member of a solidarity organization to aid the Republicans (of the Second Spanish Republic) during the Spanish Civil War (1936 to 1939). After being expelled from the Soviet Union, the former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky and his supporters saw the Communist International (also known as the Comintern or the Third International) as effectively puppets of Stalinism, and thus incapable of leading the international working class to political power. As a result, Trotskyists planned to form their own Fourth International that would be a revolutionary socialist worldwide organization made up of Trotskyists with an objective to abolish global capitalism and establish world socialism through international revolution.

Frida and Diego petitioned the Mexican authorities to grant Trotsky asylum. When they were granted asylum in Mexico, Frida and Diego gave Trotsky and his wife Natalia Sedova a place to stay at La Casa Azul (their Blue House). The pair stayed there from January 1937 to April 1939, during which Frida and Trotsky became close friends and had a brief affair. In 1938, after Trotsky founded the Fourth International (FI) in France, she joined in.

Frida and Trotsky, image source: culturacolectiva.com/history/leon-trotsky-russian-revolutionary-and-frida-kahlo-lover

17. The First Major Career Break (1937)

In 1937, a group exhibition in the Galeria de Arte at the National Autonomous University of Mexico featured four of Frida's works. Julien Levy, an American art dealer, saw the show and offered Frida a show in his Manhattan gallery to be held in the next year.

My nurse and I (1937)

‘My Nurse and I’ was one of Frida's best works, and it was included in her 1938 Julien Levy Gallery show in New York. The artist is depicted as a baby being nursed by a wet nurse in the picture. In the arms of her nurse, Frida is a newborn with an adult head. While the artwork conjures up images of the Madonna and child, it is far from tender. The nurse's face is hidden by a male Aztec funeral mask, making her appear chilly and distant. An elaborate pattern of milk glands is seen on one of the nurse's breasts, as if in a medical drawing. The structure of the enormous white leaf in the background reflects the same pattern. A praying mantis on the left and a butterfly on the right are pictured consuming milk that has fallen from the sky, feeding the lush flora. The raining milk could be interpreted as a metaphor for how Mexico's history and indigenous cultures have shaped the country's geography.

When her sister Cristina was born, Frida was unable to suckle from her mother and was instead cared for by an indigenous wet nurse. As a result, the picture might be interpreted as a reflection of Frida's relationship with her nurse, as well as a symbol of her connection to her indigenous ancestors.

Ex-votos paintings, which Catholics use to petition saints for assistance or express gratitude for a miracle, inspired Frida. The fact that Frida left the scroll blank shows that there is no redemption for her.

18. Label of ‘Surrealist,’ First Sale, and Solo Exhibition (1938)

In 1938, André Breton, the famous poet and writer from France, best recognized for being a co-founder, leader, and theorist of surrealism, and his wife Jacqueline Lamba traveled to Mexico from Paris in April to visit Leon Trotsky and stayed with Frida and Diego. Breton offered Frida an exhibition in Paris to be held in early 1939 and labeled her a Surrealist (a label that Frida later rejected).

Later that year, Diego arranged for actor and art collector Edward G. Robinson to buy four of Frida's paintings for $200 each, marking her first large sale. In October, Frida traveled to New York without Diego for her first solo exhibition. The exhibition ran from November 1 to 15, 1938, at the Julien Levy Gallery.

Surviver (1938)

In a barren landscape, the small figure appears to be lost. As a model, Frida employed an antique Mexican statue from her personal collection. According to a reviewer who saw Frida's first solo exhibition in New York, it depicts Mexico's survival in a dangerous world. Trademark Frida chose an elaborate tin frame from the Mexican state of Oaxaca on purpose.

Frida Kahlo painting the ‘Two Fridas’ by Nickolas Murray (1939)

Their hands reach out to each other for assistance, and they share a single heart. The Two Fridas, despite their differences, require each other. Frida painted several paintings in which she was split in half or shown as a double. Frida refers to her dual identity while dressed as a Tehuana mother and a European bride. She might possibly have felt "split" in her job as a wife and her inability to bear children. During her time separated from Diego, she had a series of abortions and one loss, prompting her to create this artwork.

19. The Fallout of Diego and Trotsky, Frida’s Exhibition in Paris and Affair with Jacqueline Lamba and Josephine Baker (1939)

Following personal and political differences with Diego one of which was Diego suspecting Trotsky of having an affair with Frida, Trotsky and his wife left the Blue House. Frida traveled to Paris for her exhibition that Breton had promised and lived with them. It is rumored that during this period Frida had an affair with Breton’s wife Jacqueline Lamba. It is also a popular belief and also showcased in the 2002 Hollywood movie Frida (though there aren’t concrete pieces of evidence to support the belief) that during this show Frida got into a romantic relationship with the Parisian Nightclub sensation Josephine Baker.

During the Paris exhibition, one of her paintings, ‘The Frame’, was purchased by the Louvre. This was the museum's first acquisition of a work by a Mexican artist from the twentieth century. Marcel Duchamp, Marc Chagall, and Pablo Picasso were among the artists with whom she formed friendships.

Portrait of Jacqueline Lamba, image source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacqueline_Lamba

Portrait of Josephine Baker, image source: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josephine_Baker

20. Divorce with Diego (1939)

Frida and Diego finally split up in the summer and divorced on November 6.

21. Getting Famous (1940)

The International Exhibition of Surrealism (Exposición Internacional del Surrealismo), held by Breton on January 17 in the Galera de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City, includes ‘The Two Fridas’ and her now-lost ‘The Wounded Table’. Frida's work could be seen in the exhibitions Contemporary Mexican Painting and Graphic Art at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco, and Two Fridas in the exhibition Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

22. The Assassination of Trotsky and Diego’s escape from Mexico (1940)

After the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, was assassinated in 1940 in Mexico City by Ramón Mercader, a Soviet agent allegedly sent by Stalin, Diego in fear of being held for affiliation to Trotsky, eluded Mexican authorities and gained entry to the United States with the help of the Hollywood actress Paulette Goddard, one of Diego’s lovers and a leading lady in films such as Modern Times (1936) and The Diary of a Chambermaid (1938), whose husbands included Charlie Chaplin. Diego convinced Frida to follow in his footsteps and travel to San Francisco. She attempted to flee Mexico on a temporary basis, with the visa application below but was denied. Frida and her sister Cristina were imprisoned and interrogated for two days. Despite the fact that Frida and Diego were separated at the time, they were always concerned about one another's well-being.

23. Remarriage with Diego (1940)

In September 1940, Frida traveled to San Francisco to meet her doctor, Dr. Eloesser. She had a severe renal infection, anemia, and tiredness. He advised her to go to San Francisco and join Diego. On December 8, 1940, in San Francisco, Frida and Diego reunited and remarried. Before the end of the year, Frida returned to Mexico. Diego joined her one year later.

24. End of the off-and-on Affair with Nickolas Muray

On July 2 (year unknown but could be 1941 since that is the year Nickolas got married and his affair with Frida came to an end), Nickolas wrote to Frida about his new love, “I am speaking to you now because you are the only friend - can turn to talk to, without worry - will she understand my trouble, will she not. I know you will.”

25. Detoriorating Health, Increasing Popularity and Father’s Death (1941)

Frida was commissioned by the Mexican government to paint five portraits of notable Mexican women in 1941, but she was unable to complete the project. She lost her dear father that year and continued to suffer from severe health problems. Despite her personal problems, her work became increasingly prominent, and she was featured in a number of prominent group exhibitions at that time like the one hosted by The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

26. Appointment as Teacher in Academy La Esmeralda (1942)

Frida got appointed as a teacher at the Academy La Esmeralda, a new art institution established by the Ministry of Public Education. ‘Self-Portrait with Braid’ became a part of the exhibition 20th Century Portraits at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and entered the museum's collection. Her work also featured in the Coordinating Council's First Papers of Surrealism.

Tehuacana Girl, Lucha Maria, or Sun and Moon (1942)

Lucha Maria is perched on a volcanic stone, right on the edge of day and night. Teotihuacan's ancient pyramids are dedicated to the sun and moon, and they represent Mexico's past. The toy airplane in her palm could be a reference to WWII or a symbol of the future.

Ceiling of My Home (1944)

The sun and moon, as well as the Chinese yin-yang symbol, appear frequently in Frida's art. The sun and the moon, yin, and yang, are polar opposites that complement and balance each other. Frida creates an eye in the precise middle of the page. Perhaps her statement, "It is a lovely thing to have eyes," has some significance.

Fantasy (1944)

Frida made this drawing for her patron Eduardo Morillo Safa while she was in the hospital. The patient contemplatively studies a clock that marks the slowness of time, which for Frida sometimes meant torment, in what appears to be a moment of idleness. The broken landscape culminates in two mountain-like breasts and a face with a tinge of pain in its features. The eye-clock weeps a rain that floods the land, while the veined leg above hints at the source of Frida's current discomfort: her right leg, which was in excruciating pain.

While Frida refused to be labeled a surrealist, she was aware of the stream of conscious drawing techniques prevalent among this group of painters and used them at various places in her works. "Surrealism is the magical surprise of discovering a lion in the wardrobe where you wanted to fetch a shirt," Frida said of this drawing.

Portrait of Engineer Eduardo Morillo Safa (1944)

Eduardo Morillo Safa, an agronomic, the head of Mexico City's Department of Agriculture and Public Works, and the Mexican Ambassador to Yugoslavia, Venezuela, and Panama, was one of Frida's closest friends. He commissioned Frida to paint the portraits of his wife Alicia, his daughters Lupita, Mariana, and Eduardo, as well as his mother Doa Rosita Morillo. He amassed a collection of 30 pieces by Frida throughout the years. The collection was offered to Diego after his death in 1954. Unable to afford it, Diego recommended Dolores Olmedo to purchase the paintings.

Portrait of Doña Rosita Morillo (1944)

Frida told Doa Rosita Morillo Safo's granddaughter, "The best work I ever made." You can see the sadness in the old woman's eyes, but peace and contentment prevail. Her light-colored hair resembles a halo. Frida painted a colorful background with wild leaves and branches behind the silently knitting woman. She created a sense of balance in the scene by using that contrast. Frida was influenced by the work of European artists. This painting recalls a portrait of Madame Roulin (La Berceuse) by Vincent van Gogh.

The Flower of Life (1944)

With a human flower in the shape of a womb, arms like fallopian tubes, and curves resembling a penis, complete with an orgasmic explosion of light flashes, Frida connected sexuality to nature's vital force. She infused the picture with cosmic energy by including the sun and a lightning bolt.

Untitled - Heart, Cactus and Foetus (Undated)

Fertility is a central theme in this painting, as it is in ‘Flower of Life’, and it is explored through three closely related elements in the painting: a cactus with large leaves that resemble human legs, a floating embryo connected to a cactus form by an umbilical cord, and a bleeding heart that appears to be fertilizing and giving life to the earth. A dark cloud in the sky foreshadows the fetus' uncertain destiny. The terrain is gloomy, desolate, and stark here, as it is in ‘The Broken Column’.

Diego and I (1944)

One face, two halves: Frida and Diego. However, the parts do not unite, resulting in a bizarre, hybrid entity. Between the bare branches that surround the image, the sun and the moon shine: opposites, but also symbols of male and female energy. Fertility is symbolized by shells particularly snail shells. On their fifteenth wedding anniversary, Frida gave Diego this painting as a gift.

The Broken Column (1944)

All alone, Frida stands before a landscape crisscrossed by deep ravines. She depicted her spine as a cracked, crumbling column. Valiant Frida displayed both her vulnerability and her strength. While tears run down her face, she does not cry, it is as though she has detached herself from her pain. That is how she managed to endure it and stay strong. Frida used familiar symbolism, but in her own way. With the tears and tangled hair, she was referring to La Llorona, the 'weeping woman' from Mexican legend. The nails evoke an association with the Christian Saint Sebastian, who was pierced by arrows.

Without Hope (1945)

A funnel of fatty food is pressed between Frida's lips: sausage, brains, fish, and turkey. A candy skull with her name adorns the top. She was recovering from surgery when she painted this. She'd dropped so much weight that she needed pureed food every two hours. Frida's suffering was torturous, both literally and metaphorically.

The wooden gadget on her bed, which could be an easel, seems like a rack. The massive funnel conjures up images of the Spanish Inquisition's gruesome water torture. Her sheet has a lot of cell-like shapes on it. Both the sun and the moon are visible at the same time. Her four-poster bed is nestled in a ravine-like setting. From the smallest animals to the limitless universe, Frida positioned herself in the grand scheme of things.

Self-Portrait with Small Monkey (1945)

A yellow ribbon weaves throughout the ‘Self Portrait with Small Monkey’, enveloping the artist, her beloved pet monkey, her dog Senor Xolotl, a pre-Columbian monument, and her signature. The ribbon is connected to a nail that appears to protrude from the canvas's surface, deceiving the observer and reminding them of the work's flatness. It could also mean an allusion to Jesus' crucifixion, and so to suffering and martyrdom. Frida’s dog is a xoloitzcuintli, an Aztec breed that is thought to be a spirit guide in the afterlife. In Pre-Columbian society, the monkey was a powerful emblem, representing fertility, dancing, and the arts.

The sculpture in the background represents a squatting man with a contemplative attitude and is based on an antique from Diego's collection from the state of Nayarit in Western Mexico. Frida stands goddess-like in the midst of these three figures, which are joined to her and to each other by a yellow ribbon, implying that all of these forces converge in this location.

The Mask (1945)

Frida used a mask to hide her face. She made a connection with La Malinche, a fourteen-year-old enslaved girl, as a result of this. Around 1520, she was forced to serve as a translator, mistress, and mother to the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. La Malinche has a reputation for being a traitor. Frida, on the other hand, appears to have seen her as a victim of colonialism and dominance, exploited and devastated by the Spaniards, like Mexico.

The Chick (1945)

A spherical white chick is nestled in front of a bouquet of lilacs that is enveloped in a spider's web and threatened by other insects such as caterpillars (which were regarded as death emblems) and spiders in this painting. While there isn't much written about this piece, some believe the chick is Frida, while others feel it's her husband Diego.

Appearances can be Deceiving (1946)

Underneath her Tehuana garb, a mysterious world emerged. Frida's malformed leg and her decaying spine (a column and a back brace) were hidden by her loose-fitting garments. 'Appearances can be deceiving,' she remarked beside the drawing.

Sun and Life (1947)

Frida became increasingly interested in Eastern philosophy as she neared the end of her life. Diego was depicted as the ‘sun,’ with Buddha's smile, the third eye, and the red color of the Hindu God Shiva. He hovers in front of golden-green flora shaped like embryos and vaginal openings, which are linked with the goddess Parvati. All of this resonated with Frida. Red and green, male and female, Shiva and Parvati, like Diego and Frida, are polar opposites who balance each other out.

The Embrace of Love (1949)

In this sketch, Frida explores the interconnectivity between the embraces of man and woman, day and night, and life and death. She later incorporated the concept into a painting.

Gender Fluidity (Undated)

In this self-portrait, Frida emphasizes her unibrow and moustache. We now claim that Frida did not think in terms of male or female pigeonholes, but rather welcomed gender fluidity.

27. Exploring Still Lifes (1951 - 1953)

Many of Frida's still lifes are rich in meaning, like the seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes, which she was well acquainted with. Mexican, Hindu, Catholic, and personal symbolism enlivened Frida's paintings, but the universal message of 'remember mortality' remained (memento mori).

Los Cocos or The Coconuts (1951)

The coconut appears to be crying. Frida creates a human face for the hairy fruit, conveying her personal feelings.

I belong to Samuel Fastlicht (1951)

Among Mexican fruit and the national flag is a hundreds-of-years-old statue of a Xolo dog, named after the Aztec god Xolotl. He is a symbol of death. Seventeenth-century European still-lifes, too, often feature objects that represent the finite nature of life, such as a skull or an hourglass. Frida here consciously chose a God from the ancient Mexican culture.

Still Life with Parrot and Flag (1951)

Frida used various types of Mexican fruit to show her love for her homeland. Sho also painted flowers and fruit regularly because of their sensual connotations. Mexico's flag was placed in a sliced open fruit, a mamey. It may refer to the accident in which her vagina was penetrated with a rod.

Still Life with Watermelons (1953)

Because the colors of the Mexican flag show up so well in sliced watermelons, Frida used them frequently in her paintings.

28. Leg Amputation (1953)

In August 1953, Frida's right leg was amputated at the knee owing to gangrene. She became increasingly depressed, and her painkiller addiction worsened. She attempted suicide by overdosing after Diego began yet another affair. In February 1954, she wrote in her diary, "They amputated my leg six months ago, they have given me centuries of torture and at moments I almost lost my reason. I keep on wanting to kill myself. Diego is what keeps me from it, through my vain idea that he would miss me. ... But never in my life have I suffered more. I will wait a while..."

Amputation (1953)

“Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly.” Just a month before her right leg was severed, Frida penned this under this diary artwork. Her toes are propped up on a pedestal. However, like Jesus on the cross, they are crossed. Thorny branches sprout from the right side of her leg. Probably this is how she compared her personal affliction to that of Jesus.

Wings (1953)

Frida sketched herself wearing a bandage on one leg. Her shoulders had wings growing out of them. They symbolize her inability to walk, dance, or fly. To save her life, Frida realized she needed her lower right leg amputated. But she was unsure if she could live without it. “The dove was wrong. The dove was mistaken.” Two lines from a poem by Rafael Alberti, a Spaniard.

29. Standing up again on Prosthetic Leg (1953)

Luxurious leather in a bright red hue. A blue bow with a jingling bell is embroidered with Chinese gold thread. Despite her grief after having her right leg amputated, Frida had these beautiful boots constructed. “I've had centuries of torture and at moments I nearly lost my reason,” she wrote. “I will be able to walk again, I will be able to paint again. My will remains,” she said in a poem.

30. Dancing on her Feet (1953)

“What magnificent legs! And how well they work for me,” she remarked to her friends. She did the Mexican hat dance for them in these boots - with her prosthesis - despite being heavily medicated with painkillers.

Sketch of Self-Portrait Painted for Stalin (1954)

Frida was a political activist right up until the end of her life. She aspired to use her art to promote communism, just like Diego and other Mexican muralists. During the last years of her life, she wrote about it in her journal. Joseph Stalin was depicted by Frida in a larger-than-life picture. This is a rough sketch of that artwork.

31. Weakening Resilience (1954)

But Frida's resilience was wearing thin. Despite trying to keep herself happy, Frida fell into a severe depression after losing her leg. She never fully healed. Diego said she had lost her will to live.

The Circle (1954)

After her leg was removed, Frida commented, "I am disintegration." In the year she died, she painted this self-portrait. It concentrates on her battered torso. Her head, legs, and arms are all hidden. As though Frida's heart is exploding, blood erupts from one of her breasts. Her acid-damaged body appears to be consumed by flames. Frida depicts her rotting body within a circle, a symbol of unity, perfection, and harmony.

The Final Self-Portrait (1954)

Frida created her final self-portrait in her diary, with arrows piercing her body and a stick replacing her amputated leg. She wrote a death wish on the preceding page: "Hope the exit is joyful. And I hope never to return.”

32. The End (1954)

One week after celebrating one last birthday party, Frida passed away in her home, La Casa Azul at an age of 47 years. The declared cause of death was pulmonary embolism, although several speculated that she died from an overdose, which could have been intentional or unintentional.

Frida was Frida

Frida was adamant about not being labeled. She loved to flaunt her favorite Tehuana clothes, but she also emphasized her facial hair and male features in self-portraits. "I have the moustache and the face of the opposite sex,' she explained. She had connections with both men and women, albeit she kept quiet about it. In her time, this was unusual and groundbreaking. We say today "Frida embraced gender fluidity.' She defied social expectations. Frida was Frida in every way throughout her life, remaining absolutely true to herself.

Visiting the ‘Viva la Frida’ Exhibition at Drents Museum

Address: Brink 1, 9401 HS Assen

Public Transport: The Drents Museum is only a five-minute walk from Assen's bus and train stations. Depending on where you are, take a train or a bus to the Assen Station. Then follow the Stationsstraat to the city center from the station. Cross the Oostersingel at the pedestrian crossing at the end of the Stationsstraat. In the Kloosterstraat, turn left and then right. The entrance of the Drents Museum is around the corner, at De Brink 1, at the end of the Kloosterstraat.

Car Parking: When you approach the museum, you can find a parking garage between the buildings with a sign that says ‘Parking Garage Drents Museum’ in Torenlaan. You can also park at car park Stadhuis at the Doevenkamp.

Opening Hours and Ticket Prices: For the latest information on the opening hours and ticket prices, please visit their website mentioned below.

Website: drentsmuseum.nl/en

Epilogue

So that was the story about the life and art of Frida Kahlo. Please let us know in the comments below if you liked this article. And until we meet next time, I wish you merry traveling and happy shooting!

Pin the article

Bookmark the article for reading later!

Want to license/buy photos in the article?

License photos for commercial/editorial use or buy photo prints!

Want us to write an article for you?

Articles for magazines, newspapers, and websites!

Watch our Videos

Check out our videos on our Youtube Channel!

Join the Newsletter

Get updates on our latest articles!

We respect your privacy. Read our policy here.